To watch Jacques d'Amboise, the legendary New York City Ballet dancer who died this week at the age of 86 due to complications from a stroke, coach dancers in the roles he had performed over the course of his long career was to see an artist who not only possessed formidable insight, but also exuded an infectious love of dance, and of life. To watch him interact with the young dancers of the National Dance Institute, the arts education nonprofit he created in 1976, was to see someone who passionately believed in human potential, and who thrived at seeing it realized.

D'Amboise was born Joseph Jacques Ahearn in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression. Seeking work and opportunities for their children, the Ahearns moved to New York City, soon settling in Washington Heights. Jacques' mother, whom he referred to as "The Boss," dragged him to ballet classes at the age of 7 (along with his sister Madeleine), convincing him that ballet was "magical and very hard to do," as he wrote in his 2011 memoir, I Was a Dancer. It was also The Boss's idea that the family change its name to d'Amboise, her maiden name, because, as she put it, "it's aristocratic, it's French…and it's a better name."

After a few months with a teacher uptown, he was enrolled in the School of American Ballet, along with his sister, Madeleine. The school had been founded by the recently arrived Russian émigré choreographer George Balanchine. From that moment on, the two men's lives were intertwined.

At 12, the young Jacques d'Amboise appeared with Balanchine's Ballet Society, precursor of New York City Ballet. And three years later, in 1949, he joined New York City Ballet proper, where he became the company's first homegrown male star. In his 35 years with the company, he danced in everything from Concerto Barocco to Episodes to Afternoon of a Faun. Two dozen roles were created on him, in ballets that ranged from Western Symphony, in which he played a cowboy, to Stars and Stripes, in which he was a soldier with a sparkle in his eye, to the melancholy cavalier in "Diamonds." He brought warmth to the classical roles and a convincing gusto to ballets on American themes.

Most importantly, in 1957, Balanchine revived his 1928 ballet Apollo, considered one of the pinnacles of male dancing, for d'Amboise. Though the role is that of a young god, Balanchine insisted that he dance it in the style of an "American boy, a wild untamed youth," as d'Amboise told me in a 2018 interview. Immediately after saying this, he got up to demonstrate the steps. He was then 83.

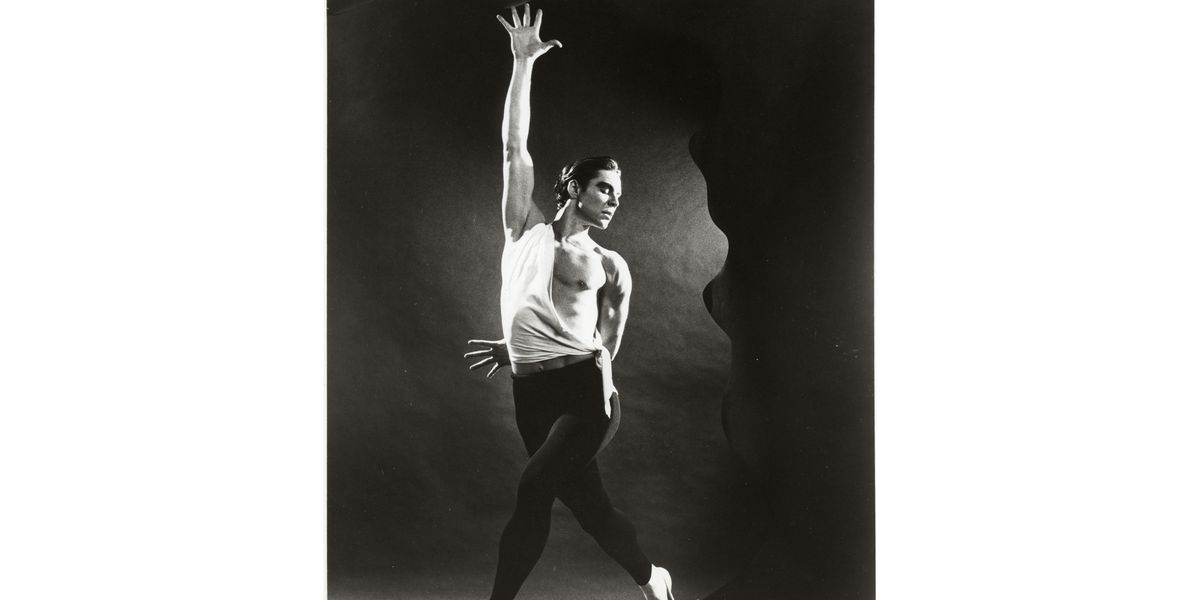

His dancing in Apollo, captured on film, was grounded, spontaneous, jazzy, angular. In a word: exciting. This unpretentious, full-blooded approach made him a star in a country that mistrusted the idea of men who danced ballet. Here was an all-American guy who could make this European art many considered effete look like breathing. In so doing, he paved the way for other accessible American male dancers, including Edward Villella, Damian Woetzel and Robert Fairchild.

His dancing also brought the art of ballet closer to American popular culture. D'Amboise performed on TV showcases like Ed Sullivan's show, and, in 1954, appeared in the Hollywood musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. That film led to others: Carousel, and The Best Things in Life Are Free.

But his commitment to ballet was steadfast, as was his devotion to his onstage partners. In his three-decade career he was the preferred partner to most of the company's leading ballerinas, including Maria Tallchief, Diana Adams, Tanaquil Le Clerq and Allegra Kent. In 1963, it was d'Amboise who spotted the young Suzanne Farrell in the corps de ballet and suggested she appear with him in a new work by John Taras, bringing her to Balanchine's attention.

D'Amboise's memoir I Was a Dancer is one of the most vivid accounts of life at New York City Ballet, and an insightful, frank portrait of Balanchine and the other figures whose lives unfolded within the walls of New York City Center, its first home, and then the New York State Theater. (He could also do a mean impression of Mr. B, as I myself have witnessed.)

While still a dancer, d'Amboise founded the National Dance Institute, a program that brings dance education to kids in public schools. Over the last 45 years, it has reached more than 2 million children. After his retirement, NDI became d'Amboise's great passion, to which he dedicated his formidable energies. The offices of NDI, on West 147th Street, were where he could be found most days.

As Harrison Coll, a dancer at New York City Ballet who was mentored by d'Amboise from the age of 19, recently put it in an Instagram post. "The man lived LARGE and with the most open and loving heart."

from Pointe https://ift.tt/33ef6cd

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق