The Nutcracker has been a dancer's tradition for over 125 years. As a student at Russia's Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburg in the early 1900s, a young George Balanchine performed in the original production of The Nutcracker, created in 1892, at the Imperial Mariinsky Theater. In fact, that production had a huge influence on his own version, choreographed in 1954 for the New York City Ballet—and now performed at Christmastime by companies across the nation and abroad.

In 2013, Russian choreographers Vasily Medvedev and Yuri Burlaka staged a revival of the original Mariinsky production for Staatsballett Berlin, based on the 1892 libretto by Marius Petipa, choreography by Lev Ivanov and original set and costume designs. Using a combination of Stepanov notations and early film recordings of Nikolas Sergeyev's first stagings of the ballet in the West, Medvedev and Burlaka built a version of The Nutcracker. Though not a step-by-step reconstruction, their production transmits the original's "unmistakable flair," as they explain in the program notes. Pointe took a look at both the Berlin and New York productions to see how Balanchine's childhood Nutcracker might have influenced his own. We found a lot of similarities—and a few key differences.

Lots of Children

One thing is for sure; both productions feature tons of students: over 125 in two alternating casts from the School of American Ballet in New York, and around 60 from the State Ballet School of Berlin. "Children play the main roles in this fairy tale," Burlaka and Medvedev explain in their program notes. Students appear in both productions as party guests, soldiers, angels, polichinelles, candy canes (or bouffons, as the original production calls them) and beyond. In both party scenes, students perform rousing games and social dances—though they are a few years older in Berlin; polichinelles are similarly spritely, and angels walk with the same tiny shuffles to mimic floating in both productions. And to our delight, both versions feature an adorable bunny rabbit soldier.

Lots of Children

One thing is for sure; both productions feature tons of students: over 125 in two alternating casts from the School of American Ballet in New York, and around 60 from the State Ballet School of Berlin. "Children play the main roles in this fairy tale," Burlaka and Medvedev explain in their program notes. Students appear in both productions as party guests, soldiers, angels, polichinelles, candy canes (or bouffons, as the original production calls them) and beyond. In both party scenes, students perform rousing games and social dances—though they are a few years older in Berlin; polichinelles are similarly spritely, and angels walk with the same tiny shuffles to mimic floating in both productions. And to our delight, both versions feature an adorable bunny rabbit soldier.

Lots of Children

One thing is for sure; both productions feature tons of students: over 125 in two alternating casts from the School of American Ballet in New York, and around 60 from the State Ballet School of Berlin. "Children play the main roles in this fairy tale," Burlaka and Medvedev explain in their program notes. Students appear in both productions as party guests, soldiers, angels, polichinelles, candy canes (or bouffons, as the original production calls them) and beyond. In both party scenes, students perform rousing games and social dances—though they are a few years older in Berlin; polichinelles are similarly spritely, and angels walk with the same tiny shuffles to mimic floating in both productions. And to our delight, both versions feature an adorable bunny rabbit soldier.

Lots of Children

One thing is for sure; both productions feature tons of students: over 125 in two alternating casts from the School of American Ballet in New York, and around 60 from the State Ballet School of Berlin. "Children play the main roles in this fairy tale," Burlaka and Medvedev explain in their program notes. Students appear in both productions as party guests, soldiers, angels, polichinelles, candy canes (or bouffons, as the original production calls them) and beyond. In both party scenes, students perform rousing games and social dances—though they are a few years older in Berlin; polichinelles are similarly spritely, and angels walk with the same tiny shuffles to mimic floating in both productions. And to our delight, both versions feature an adorable bunny rabbit soldier.

Larger Than Life Sets

Marvelous sets take center stage in both productions. In Balanchine's version, a Christmas tree designed by Rouben Ter-Arutunian grows to massive proportions during one of the most dramatic musical moments. Andrei Voytenko's sets in Berlin (after the 1892 originals by Konstantin Ivanov and Mikhail Botscharov) create a similarly impressive effect. Both versions feature giant furniture in the battle scene—a bed in Balanchine's and an arm chair in Medvedev/Burlaka's. And though true of many productions, sets for the Lands of Sweets in both New York and Berlin overflow with enticing confections.

Larger Than Life Sets

Marvelous sets take center stage in both productions. In Balanchine's version, a Christmas tree designed by Rouben Ter-Arutunian grows to massive proportions during one of the most dramatic musical moments. Andrei Voytenko's sets in Berlin (after the 1892 originals by Konstantin Ivanov and Mikhail Botscharov) create a similarly impressive effect. Both versions feature giant furniture in the battle scene—a bed in Balanchine's and an arm chair in Medvedev/Burlaka's. And though true of many productions, sets for the Lands of Sweets in both New York and Berlin overflow with enticing confections.

Larger Than Life Sets

Marvelous sets take center stage in both productions. In Balanchine's version, a Christmas tree designed by Rouben Ter-Arutunian grows to massive proportions during one of the most dramatic musical moments. Andrei Voytenko's sets in Berlin (after the 1892 originals by Konstantin Ivanov and Mikhail Botscharov) create a similarly impressive effect. Both versions feature giant furniture in the battle scene—a bed in Balanchine's and an arm chair in Medvedev/Burlaka's. And though true of many productions, sets for the Lands of Sweets in both New York and Berlin overflow with enticing confections.

Snowflakes With Pom-Poms

With no Snow Queen or King in either version, the corps leads the snow scene. The dancers (16 in New York and 24 in Berlin) stir up flurries with their precise pointe work, quick runs and charged energies; for the Berlin version, the Stepanov notations indicated floor patterns and snapshots of Ivanov's choreography, and Medvedev and Burlaka filled in the transitions. To top it off, dancers hold pom-poms in their hands in both versions, shaking their fists to mimic shivering in Berlin and flicking their wrists in New York in time with the music, resulting in two similarly dazzling winter wonderlands.

Snowflakes With Pom-Poms

With no Snow Queen or King in either version, the corps leads the snow scene. The dancers (16 in New York and 24 in Berlin) stir up flurries with their precise pointe work, quick runs and charged energies; for the Berlin version, the Stepanov notations indicated floor patterns and snapshots of Ivanov's choreography, and Medvedev and Burlaka filled in the transitions. To top it off, dancers hold pom-poms in their hands in both versions, shaking their fists to mimic shivering in Berlin and flicking their wrists in New York in time with the music, resulting in two similarly dazzling winter wonderlands.

Snowflakes With Pom-Poms

With no Snow Queen or King in either version, the corps leads the snow scene. The dancers (16 in New York and 24 in Berlin) stir up flurries with their precise pointe work, quick runs and charged energies; for the Berlin version, the Stepanov notations indicated floor patterns and snapshots of Ivanov's choreography, and Medvedev and Burlaka filled in the transitions. To top it off, dancers hold pom-poms in their hands in both versions, shaking their fists to mimic shivering in Berlin and flicking their wrists in New York in time with the music, resulting in two similarly dazzling winter wonderlands.

The Prince's Pantomime

Balanchine danced the role of the Prince himself in 1919, at 15 years old. So it's no wonder that both versions include a pantomime in which the Prince tells the story of his battle against the Mouse King. Even though Balanchine's prince is a young boy, while Medvedev/Burlaka's is a principal dancer (adjusted from the original to dance the pas de deux with Clara later in the ballet), both versions use similar movements to tell the story: marching, lunging, waving an imaginary sword, and quick scurrying runs to depict the Mouse King.

Details in Divertissements

Act 2 divertissements share many similarities, partly due to the gorgeous costumes—designed by Tatiana Noginova after the Ivan A. Vsevolozhsjy originals in Berlin, and Karinska in New York. Dancers in the Mirliton/Marzipan dance wear yellow pointe shoes, dancing similarly sumptuous pointe work while holding small props—a pan flute in New York and baton in Berlin; The Danse orientale (Coffee) features a male soloist in Berlin, just as it did in New York originally, though now the solo is performed by a woman. And the Candy Canes hoop dance in New York, a man's solo framed by a corps of students, is remarkably similar to the show-stopping Danse des bouffons in Berlin.

Details in Divertissements

Act 2 divertissements share many similarities, partly due to the gorgeous costumes—designed by Tatiana Noginova after the Ivan A. Vsevolozhsjy originals in Berlin, and Karinska in New York. Dancers in the Mirliton/Marzipan dance wear yellow pointe shoes, dancing similarly sumptuous pointe work while holding small props—a pan flute in New York and baton in Berlin; The Danse orientale (Coffee) features a male soloist in Berlin, just as it did in New York originally, though now the solo is performed by a woman. And the Candy Canes hoop dance in New York, a man's solo framed by a corps of students, is remarkably similar to the show-stopping Danse des bouffons in Berlin.

Details in Divertissements

Act 2 divertissements share many similarities, partly due to the gorgeous costumes—designed by Tatiana Noginova after the Ivan A. Vsevolozhsjy originals in Berlin, and Karinska in New York. Dancers in the Mirliton/Marzipan dance wear yellow pointe shoes, dancing similarly sumptuous pointe work while holding small props—a pan flute in New York and baton in Berlin; The Danse orientale (Coffee) features a male soloist in Berlin, just as it did in New York originally, though now the solo is performed by a woman. And the Candy Canes hoop dance in New York, a man's solo framed by a corps of students, is remarkably similar to the show-stopping Danse des bouffons in Berlin.

The Sugar Plum Fairy's Magical Moment

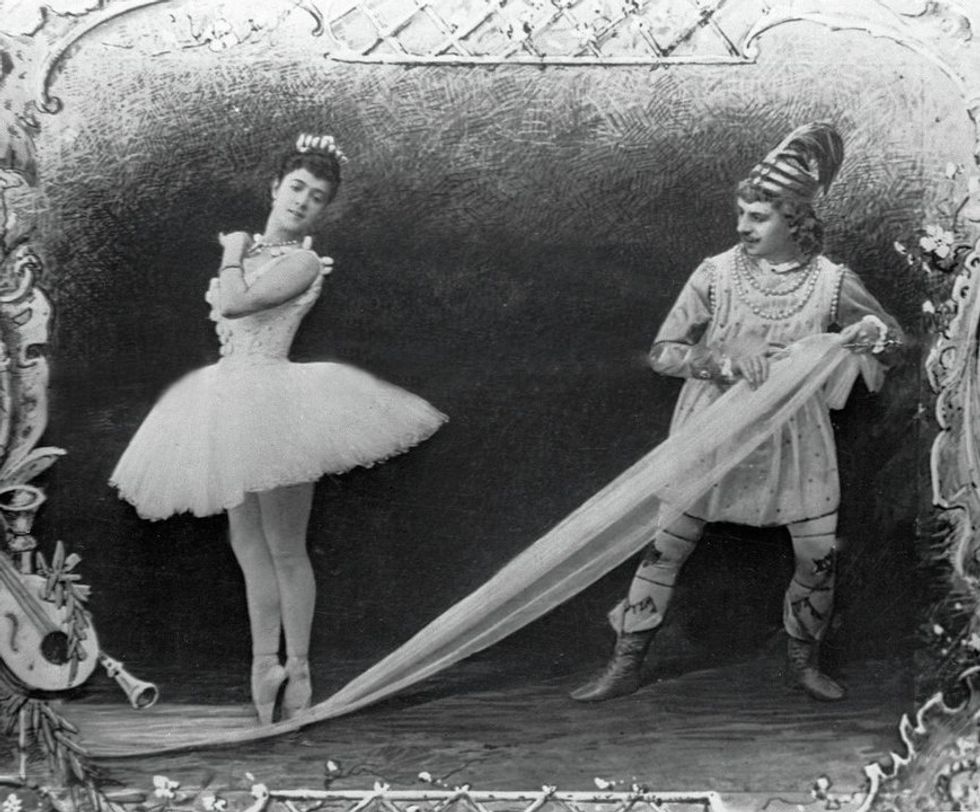

Petipa's libretto described the ballet as a ballet-féerie—historically, a ballet that depicts a fantasy world. In the St. Petersburg original, Italian prima ballerina Antonietta Dell'Era danced the role of the Fée Dragée (aka, Sugar Plum Fairy). Medvedev and Burlaka adjusted the role by replacing both Clara and the Prince with professional dancers at the end of Act I, to allow Clara to live her fantasy by becoming the Fée Dragée and dance the Grand Pas de Deux with her prince.

While Balanchine's pas de deux choreography differs greatly from that in the Berlin production, both showcase a climactic moment where the ballerina slides across the stage on the tip of her pointe, led by her cavalier. She stands on a disk Balanchine's, and on a white gauze scarf in Medvedev/Burlaka's.

The Sugar Plum Fairy's Magical Moment

Petipa's libretto described the ballet as a ballet-féerie—historically, a ballet that depicts a fantasy world. In the St. Petersburg original, Italian prima ballerina Antonietta Dell'Era danced the role of the Fée Dragée (aka, Sugar Plum Fairy). Medvedev and Burlaka adjusted the role by replacing both Clara and the Prince with professional dancers at the end of Act I, to allow Clara to live her fantasy by becoming the Fée Dragée and dance the Grand Pas de Deux with her prince.

While Balanchine's pas de deux choreography differs greatly from that in the Berlin production, both showcase a climactic moment where the ballerina slides across the stage on the tip of her pointe, led by her cavalier. She stands on a disk Balanchine's, and on a white gauze scarf in Medvedev/Burlaka's.

The Sugar Plum Fairy's Magical Moment

Petipa's libretto described the ballet as a ballet-féerie—historically, a ballet that depicts a fantasy world. In the St. Petersburg original, Italian prima ballerina Antonietta Dell'Era danced the role of the Fée Dragée (aka, Sugar Plum Fairy). Medvedev and Burlaka adjusted the role by replacing both Clara and the Prince with professional dancers at the end of Act I, to allow Clara to live her fantasy by becoming the Fée Dragée and dance the Grand Pas de Deux with her prince.

While Balanchine's pas de deux choreography differs greatly from that in the Berlin production, both showcase a climactic moment where the ballerina slides across the stage on the tip of her pointe, led by her cavalier. She stands on a disk Balanchine's, and on a white gauze scarf in Medvedev/Burlaka's.

Differing Tempi

In many instances, tempi in Balanchine's production are much faster. In Berlin, the doll dance, primarily a pas de deux between the Puppet Prince and Princess, is almost half the speed. The Snow Scene, along with the Coffee, Tea, and Flowers divertissements are all considerably quicker in New York. This is the place where Balanchine appears to have diverged most from his roots; his version of The Nutcracker reflects the swiftness of the American pace.

from Pointe https://ift.tt/35Zhsvs

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق